Illustration by Rucsandra Enache

Sustainability: A Historical Approach of a "New" Concept

Oana Ivan

Abstract

The concept of “sustainability” is a must today: from the tiniest farming product or restaurant menu, to the multi-million-euro budget projects, “sustainable” needs to be on the front cover, on the label, in the main title. We got so used to the term that we hardly ever think what it actually means. The present essay discusses one of the most used misconceptions of sustainability in relationship to the “good old days” when life was said to be simpler, care free and consumerism was unheard of. The present essay uses the centuries-long history of fishing in an UNESCO biosphere reserve, the Danube Delta, to de-construct this myth. It questions whether “sustainability” can so easily go hand in hand with “tradition” and whether local people using natural resources, (in this case, the fish) were actually living in harmony with nature since the dawn of time. Colonial powers, international markets and politics are deeply shaping the ways locals are using the natural resources.

AnthroArt Podcast

Oana Ivan

Author

Oana Ivan is an anthropologist specialized in visual anthropology and environmental anthropology (following her PhD under joint supervision at the University of Kent, UK and Babeș-Bolyai University, Romania). She is also a director and producer of anthropological documentary films focused mainly on the interaction between human communities and the natural environment. Her research area includes in particular the protected natural areas of the Danube Delta, the Danube Meadows, the Eastern Carpathians, the Transylvanian Plateau and the Apuseni Mountains. She is currently a lecturer in the Documentary Film Department of the Faculty of Theater and Film – Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj. She is also a consultant and collaborator in various research projects of: National Geographic, World Bank, Electric Castle.

Rucsandra Enache

Illustrator

Rucsandra Enache is a visual artist specializing in graphic novel illustrations. She manages to reveal the imaginary intimate universe through her works, empasizing the state of introspection, her fantastical creatures purely made out of her imaginations in her numerous projects. Rucsandra finished her master degree in graphics at National University of Arts in Bucharest and now is working in collaboration with diferent Romanian NGOs.

Katia Pascariu

Actress / Voice

Katia Pascariu is an actress and a cultural activist. She studied Drama & Performing Arts at UNATC, obtaining her BA in 2006, and got her master’s degree in Anthropology in 2016 at the University of Bucharest, where she currently works and resides. She is part of several independent theatre collectives that do political and educational projects – Macaz Cooperative, 4th Age Community Arts Center and Replika Center, with special focus on multi- and inter – disciplinarity. She develops, together with her colleagues, artistic and social programs, in support of vulnerable and marginal communities, while promoting socially engaged art, accesibility to culture, with a main focus on: education, social justice, recent local history. She has been part of the casts of Beyond the Hills (C. Mungiu, 2012) and Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn (R. Jude, 2021), among others. She is working also within the artistic ensemble of the Jewish State Theatre in Bucharest. She performs in Romanian, English, French and Yiddish.

The concept of “sustainability” is a must today: from the tiniest farming product or restaurant menu, to the multi-million-euro budget projects, “sustainable” needs to be on the front cover, on the label, in the main title. We got so used to the term that we hardly ever think what it actually means. The present essay discusses one of the most used misconception of sustainability in relationship to the “good old days” when life was said to be simpler, care free and consumerism was unheard of.

The image of Romania is often presented to the Westerner tourists as a “land lost in time, where man has lived in harmony with nature since the dawn of time” (Ottley 2011). This imagery is feeding the nostalgia for pristine nature and pretty villages of heavily industrialized and technologized Europeans. The same feel of nostalgia is also very present in the very polluted and overcrowded big Romanian cities. Urban people are longing for fresh air and tasty food produced by local farmers and tend to have an idyllic picture of life in the countryside in past:: “Our grand and great-parents were not stressed out, they were living of the farm consuming only what they needed and they were happier” is an idea shared by many Romanians living in urban areas.

The concept of local or indigenous people living in harmony with nature that created the myth of the “noble savage” in the 17th century, describing the local/ indigenous people not corrupted by civilization, is making a strong come back for the past decade. Western Europeans are increasingly looking at Romania as a “pristine piece of heaven” while urban Romanians are looking at those who live in the countryside as the keepers of “sustainable and traditional old ways”.

The present essay uses the centuries-long history of fishing in an UNESCO biosphere reserve, the Danube Delta, to de-construct this myth. It questions whether “sustainability” can so easily go hand in hand with “tradition”and whether local people using natural resources, (in this case, the fish) were actually living in harmony with nature, before consumerism spoiled the pristine heaven of the Danube Delta. The historical examples discussed bellow reveal in some cases extreme ways of natural resource depletion practiced a few centuries ago. However, the aim of this essay is NOT to put a blame on the local people and NOT to show that they are destroyers of nature. Local communities have a crucial role in sustainable use of resources and their traditional ecological knowledge should be at the center of ecological programs, as proved by multiple studies.

The very aim of this paper is a call to de-construct the idea of sustainability as an inherent feature of the ”traditional old ways” and to raise awareness on the need of understanding the past practices of natural resource use in the context of their times. Instead of having a romanticized perception of the past and trying to bring back to life an image that was actually never real, we should look at the past through the lens of critical thinking. This implies understanding the political and economical context and the pressures put by various regional or international institutions upon the local people. This discussion is not new -, it has been carried out for decades in anthropological circles, but the wider audience was hardly ever part of the conversation.

This paper is based on a PhD anthropological research carried out by the author under the tutelage of University of Kent and Babes-Bolyai University, and relies on two main methods and sources: archival records, especially eco-system analysis made in the 1900s by

Dr. Grigore Antipa (student of Ernst Haeckel, the “father” of ecology) and field research, mainly participant observation and interviews, with Danube Delta fishermen between 2010 and 2021. Reiterating the need to understand the local practices in the greater political-economic context of their times and NOT creating new stereotypes such as “locals: ax handles, destroyers of nature without global consciousness”, the following paragraphs will present a brief history of fishing techniques and modes of natural resource use in the Danube Delta describing them in relation with the governing political and economic systems of their times. Let’s take a look on what was “before”, when life was (said to be) simpler and people are(seen as) living in harmony with nature.

Fishing in the Middle Age and during the Ottoman Empire (1500-1800)

The richness of the fish in the Danube Delta and the intense exploitation at the ”Danube’s mouths” are mentioned in the year 950 AD, in the documents of the Byzantine emperor Constantin Porfirogenet, where the settlements of Sulina and Sfântu Gheorghe were identified as the main centers for fishing and navigation (Giurescu 1965). Fishing was one of the main subsistence activities, and fish was very important in the Orthodox states because fish and its caviar was the only meat allowed (on designated days) over the long religious fasting periods (Romania had as many as 202 fast days in a year). Moreover, livestock was consumed in spring or winter time, while fish remained available all year (Antipa 1895). Consequently, the high demand for this product created in the 12th century a “fish road” starting in Dobrogea and reaching all the main Russian cities, the Byzantine Empire, Greece and the Hapsburg Empire (Giurescu 1965). The settlements at the Danube’s mouth were well connected to the big cities of the surrounding Empires, stretching on two continents. As early as 12th century, Danube Delta fishermen were providing for international markets, and the mode of resource use was designed to follow the international “fish road” and not the small scale and domestic consumption.

After the Ottoman conquest of Dobrogea’s cities in 1484, the head of the Empire, the Sultan, took immediate actions to regulate the fishing, as it represented an important source of income for his Empire. The rivers, channels and lakes could be leased by the free people in exchange for a lease tax and a percentage of the catch. Long-term, sustainable fishing was not possible as the lease would last for a period of 5 years and the leaser’s main interest was to catch as mush as possible during that time and cover the high taxes. “Hit and run” strategy.

Sturgeon fishing was no better. In the springtime, under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, fishermen used to stick wooden poles all across the Danube River, leaving just a narrow opening for ship navigation, creating a wooden dam. The temporary wall strong enough to even hold coffee houses on it, would catch all the migrating sturgeons from the Black Sea. Between spring and winter time, fishing was so intense that it was leaving the sturgeon population no time to recover. The captured fish was traded along the old trade routes, making the lease holders and the Ottoman government very rich (Alexandrescu- Dresca Bulgaru 1971).

Modern Romania (before WW2)

In 1877, after almost 500 years, Dobrogea regained its freedom from the rule of Ottoman Empire and became a Romanian territory. In 1894, Grigore Antipa, the Romanian scientist and student of Ernst Haeckle – the father of modern ecology, published a report on the Danube’s Delta fisheries. Antipa claimed the disastrous situation of the fish catch was a direct consequence of the “barbarian way” of fishing under the rule of the Ottoman Empire: the 5 year lease, the very dense fishing nets, the unrestricted fishing during the mating season (Antipa 1894).

He also emphasized the role of fishing practices and fishermen who seek immediate profit and neglect the sustainable use of the resources, although the fishermen’s community suffered most from this situation: the number of fishermen dropped along with the capture, and some of them turned to agriculture or moved out. The fishermen admitted that while 20 years before they used to capture 200 kilograms/year, in 1880s this has decline to only 80 kilograms/year. The sturgeons used to be able to migrate up the Danube, reaching Bavaria, but again in 1880s, this was almost impossible due to the “savage fishing” at the Danube’s mouth, during the Ottoman rule.

Under these circumstances, Antipa proposed a set of regulations such as limits to fishing during the mating season, the management of the waters by the Romanian State and not through the leasing system, and limits to the drainage and damming of the channels (Antipa 1894). The new regulations proved effective and five years later the sturgeon capture rose 600% (Antipa 1899).

Beginning with the 1900s, Antipa had did extensive research in the Danube Delta, analyzing the ecosystems and observing the fishermen’s life. With the support of the Romanian king, Carol II, Antipa succeeded in revitalizing the Danube’s Delta fisheries and turning fishing into a modern industry based on science.

Fish exploitation was directly tied to the demand of fish of the market in Galați. Most of the fishermen lacking capital and tools, were employed by a “hazeain” (master in Ukr. language) and according to the present days fishermen, the “hazeain” was interested in providing high number of fish to the market (especially sturgeon), in order to maximize his profit. Besides working for the “hazeain”, fishermen would also catch fish for domestic consumption, but most of the fishing was following the logic of the market until the second World War.

In 1937, Antipa proposed the application of a coherent 50-year master-plan that would solve the new problems that arose such as: poor management of the state’s institutions in charge with fishing business, excessive bureaucracy, managers’ lack of deep knowledge and understanding of the Delta’s reality, and corruption among the clerks who managed profitable resources in the Danube Delta. On the other hand, discontent among fishermen grew as they resented the restricted fishing periods, during which they were mostly unemployed and thus accrued great debts to the traders. As might be expected, this situation led to increased poaching (Antipa 1937).

Changing state regulations brought by the shift from an Ottoman Empire colony to modern Romania had a dramatic impact on the fishing methods and the use of natural resources, as emphasized above. Through this example we can see once more how the political and economic system can put tremendous pressure on who in return put pressure on the resource, in order to be able to pay the debts to the hazeain who would lend them the money during the periods of restricted fishing.

1950s and onwards

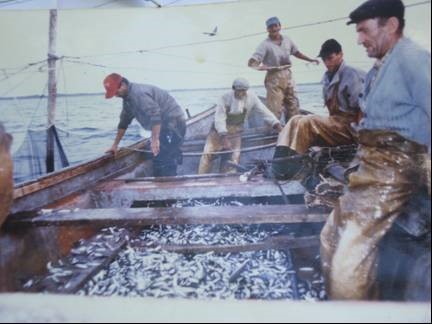

After World War II, Romania was under the communist regime, which prioritized the exploitation of resources, following an ambitious plan for industrialization and modernization of the country. The government exerted strict control over natural resources, establishing state-owned enterprises responsible for resource extraction, processing, and distribution. In this context, the Danube Delta made no exception. Due to its various and abundant natural resources, the Danube Delta suffered dramatic changes.No less than 80 thousands hectares of wetlands were reclaimed for agriculture, fish farming and forestry. The environment was transformed by intense fish farming, cattle breeding, agriculture, reed exploitation and channel clearing (Dumitrescu 2002). In the meantime, the fishermen were employed by Piscicola, the state-owned fishing enterprise, in charge with all aspects of this enterprise, from organizing the fishing teams and investing in tools and technology, to creating a unique, state-owned, fish market.

In this context, fishermen had little to almost no agency and they had tofollow Piscicola’s long-term plan for intense fishing and resource exploitation. According to the local fishermen, Piscicola learned most of the fishing techniques and modes of resource use from the elders and upscaled it 10 times. For almost half a century, fishing in the Danube Delta was completely organized and controlled by the state, supporting once again the argument that political and economic systems shape dramatically the modes of resource exploitation. Understanding the context makes us more careful about how we use the term “in the past” when we talk about the “good old days”.

UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and present times

After the fall of communism in 1989, the Danube Delta became important for the international scientific world and a major shift occurred: it became a strictly protected area as a biosphere reserve. The Delta’s regime turned from the reclamation program and intensive exploitation of the natural resources to the sustainable development approach (Dumitrescu 2002). In 1991, the Romanian part of the Danube Delta became part of UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites. Around 2,733 km² of the delta are strictly protected areas.

Regarding the fisheries, as Romania became a democratic and capitalist country, the fishing returned to the logic of market and competition, with fishermen organizing themselves in teams and investing high sums of money in tools and new fishing techniques. New (and not so new, as they have been already mentioned by Antipa 100 years ago) problems occurred: poaching, corruption, pressure from market and tourism (Ivan 2016), National institutions such as the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve Authority and or international ones such as the E.U. or the global fish market are the main players shaping the way fishing is carried out today in the Danube Delta.

Conclusions

A very brief look over the past one thousand years of fishing in the Danube Delta paints a very different picture than the stereotype of “People living in harmony with nature since the dawn of times”. One can hardly talk about sustainability for almost 500 years with “the barbarian way of fishing” (Antipa 1894), depleting the resource, while being a colony under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. Connections to international markets for more than a millennium dramatically shaped the way fishing was done, de-constructing once more the idyllic image of the local people in their own self-sufficient, care free, little universe. Modern history also emphasizes the role of national and international institutions in enforcing fishing regulations and modes of extraction. As usually, history teaches us a lesson for the future. In this case it would be a call for a good understanding of the local context and the pressures from the political and economic system governing the way people extract the natural resources. Proposing sustainable programs for the future relying on a romanticized picture of the past or on stereotypical images of local people, while ignoring policies, economics and politics, can be doomed to fail from the start.

References

Alexandrescu-Dresca Bulgaru, M.M. 1971. Pescuitul in Delta Dunarii in vremea stapanirii otomane. Peuce-studii si comunicari de istorie, etnografie si muzeologie. Tulcea: Muzeul Deltei Dunarii.

Antipa, Grigore. 1894. Lacul Razim. Bucuresti: Imprimeria statului

____________. 1895. Studii asupra pescariilor din Romania. Bucuresti: Imprimeria statului

____________. 1899. Legea pescuitului si rezultatele ce le-a dat. Bucuresti: Institutul de Arte Grafice si Editura Minerva

____________. 1916. Pescaria si Pescuitul in Romania. Bucuresti: Academia Romana

____________. 1932. Marea noastra. Extras din Boabe de grau III. Bucuresti

____________. 1937. Memoriu privitor la aplicarea unui plan cincinal pentru desvoltarea pescariilor statului. Extras din Buletinul Administratiei. Bucuresti

Dumitrescu, Ana. 2002. The impact of the social and economic policies on the local people of the Danube Delta and the necessary measures. Scientific annals of the Danube Delta Institute. Bucuresti: Editura Tehnica.

Giurescu, Constatin. 1965. Istoria Pescuitului si Pisciculturii in Romania. Bucuresti: Ed. Republicii Populare Romane.